The architecture teachers at KLE Tech are really enthusiastic about teaching and about learning to do educational research. A number of them attended the engineering education conferences held at their institution in January — the IUCEE conference on engineering teaching and REES, the Research in Engineering Education Symposium, which focuses on research about engineering teaching.

KLE Tech’s lovely Dipanwita Chakravarty was the most enthusiastic among them, delighted as she was to find an architect speaking on a panel at REES.

That architect was me! 🙂

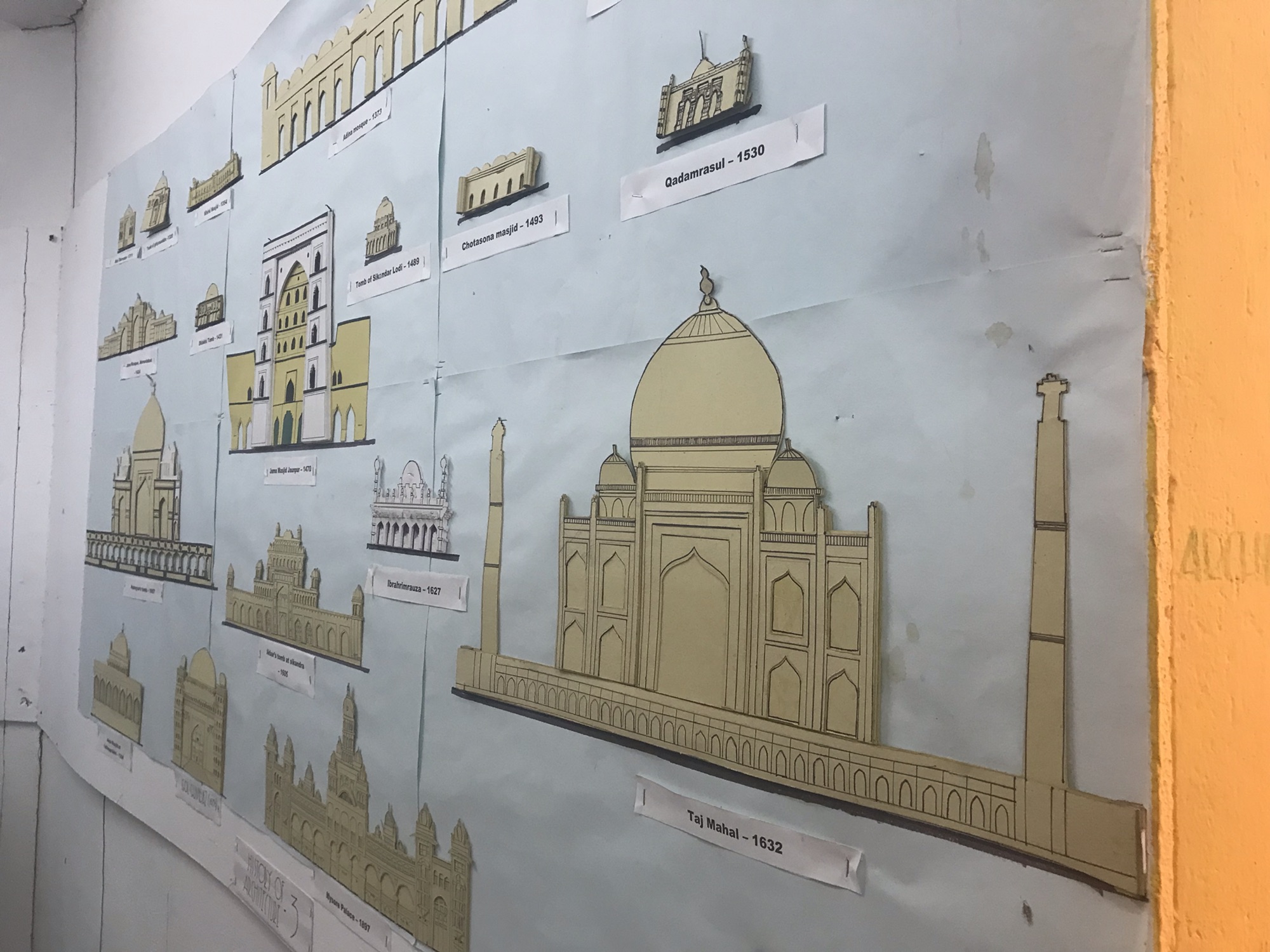

Dipanwita found me soon after I presented, asking me to meet her architecture colleagues. She spirited me away from the events at REES, to meet Deepa Mane and Rohini Mligi, tour a room archiving their architecture students’ work, and then meet even more colleagues for an animated chat about research and curriculum design. And tea! Such excellent tea!

Here’s a glimpse of that afternoon’s tour and interactions:

In that initial discussion in their faculty boardroom, we talked about different types of research they are doing and their interests surrounding architectural accreditation.

They asked me to help them build momentum and capacity to do education research, as they were enjoying seeing work presented at REES but were not quite sure how this type of research would look in the context of architecture rather than engineering.

We decided we needed a group identity. We envisioned collaborating with the engineering education research center on their campus (which has its own building, as it’s the leader in this realm in India). We also envisioned becoming active members of India’s IUCEE (the corollary of ASEE or SEFI for India).

As a step forward, we asked Dr/Prof Vijayalakshmi M., one of the main organizers of IUCEE and this event, if we could start a special interest group for architecture (and design?) within IUCEE. She was supportive. She gave us the Indian head shake and said: sure, just get started, and let’s see how it grows!

It was a very satisfying exchange, and I returned to REES for the day, happy and energized. I toured KLE Tech’s building for technical engineering later that day alongside the always-smiling, always-energetic Dipanwita Chakravarty and my colleagues from near and far.

The next morning, the architecture staff spirited me away again!

They’d assembled an even larger group to discuss what education research is, how education research differs from technical research on architecture and engineering (like the work they are already doing on thermal comfort and architectural heritage conservation), and how they can get started doing this new type of research.

Here are the lovely photos they took of that impromptu seminar along with a photo of our whole group after that meeting.

You can see they made me feel like a rock star! The meeting was so much fun.

We’ve had a gap in communication since the conference ended, because I was on the lecture circuit (lol!) and then getting caught up back home and inducting a new cohort of BIM BSc students.

But my KLE architecture colleagues and I plan to hold online meetings in the near future to discuss examples of educational research in architectural education. I’ve agreed to help them envision, plan, and get started conducting education research.

One of the architects in the group emailed me later, asking me to share my own examples.

Reflecting on this request, I fear my own examples in this realm pale in comparison to my engineering education research. Architecture teachers tend to publish conference papers showing how they taught their class, and of these, my favorite among my papers reporting what might (optimistically) be called research-informed teaching or the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) would probably be Writing Architecture: The Role of Process Journals in Architectural Education and Beginning with Site in Architectural Education.

However, engineering education research is more rigorous than SOTL.

Although ‘engineering education’ conferences will allow the publication of reports on ‘how I taught my class’, the ‘engineering education research’ journals want empirical research studies. You have to collect and analyze data in a rigorous way. An example of this type of work is the book chapter Designing the Identities of Engineers, for which I collected surveys and compared results statistically between ‘engineering’ and ‘engineering technology’ students. The biggest difference I found, and my team reported, was that the ‘engineering’ students envisioned themselves as designers, whereas the ‘engineering technology’ students did not.

Another worthwhile example is my conference paper, where I first reported the design of the study as the Background and Design of a Qualitative Study on Globally Responsible Decision-Making in Civil Engineering and then published the results in a few different ways. The journal article Above And Beyond: Ethics And Responsibility In Civil Engineering reports what the civil engineers I spoke with discussed about ethics, whereas Opportunities and barriers faced by early-career civil engineers enacting global responsibility provides a more holistic report of what we found overall. The official ‘industry’ report of the study is called the Global Responsibility of Engineering Report and it was published by Engineers without Borders UK.

My primary research group, the European Society for Engineering Education (SEFI), embraces architects as if they are engineers, which is a reason I identify so strongly with SEFI. Yet, SEFI doesn’t have a special interest group in architecture or architectural engineering, even though the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) does have an Architectural Engineering division. ASEE’s Journal of Engineering Education rarely publishes research on architecture education.

In contrast, SEFI’s European Journal of Engineering Education, for which I am Deputy Editor, has been reviewing an increasing number of articles on architecture and construction-related topics in education. I suspect that’s partially because I have the interest, capacity, and collegial networks to help support such articles’ review, refinement, and publication. But I also have amazing mentors in my Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Kristina Edström, and co-Deputy Editor, Dr. Jonte Bernhard. They are encouraging me to build capacity in this realm. And they understand that building the cadre of reviewers with expertise in this area takes time, patience, and much enthusiasm!

Our merry band of editors has ample patience and enthusiasm!

[Edit after posting: SEFI just launched a new journal that does publish SOTL papers, see: https://sefi-jeea.org/index.php/sefijeea/announcement/view/1! It says, “The SEFI Journal of Engineering Education Advancement offers a route to share ideas, emerging research, practice experience and innovations in the engineering education field.”]

In reflecting on what publications I have of my own that truly relate to architecture, I have identified Using Architecture Design Studio Pedagogies to Enhance Engineering Education as a favorite of mine. Unfortunately, it isn’t easy to find on search engines and the platform to download it is far from user-friendly. It doesn’t get the attention it deserves, but you can download it by clicking the title and see how you like it!

Another relevant work of which I am very proud is Comparing the meaning of ‘thesis’ and ‘final year project’ in architecture and engineering education. Yet this paper is more conceptual than empirically based and, thus, isn’t the best place to start the discussion with my colleagues at KLE Tech. I am delighted to report that it’s garnered nearly 1300 views since it was published, just 5.5 months ago.

A good place to start our discussion might actually be Comparing Grounded Theory and Phenomenology, an article I think is one of my best but has a very long and obscure title that I haven’t bored you with here!

My KLE Tech colleagues have a keen interest in architecture accreditation. These days, I am more engaged with engineering accreditation than with architecture accreditation (having uploaded a conference paper earlier today on engineering ethics accreditation, in fact). But in the past, I’ve been quite involved with the USA’s National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB), and my colleagues at KLE Tech are using NAAB’s guidelines to help them structure their programs. One day, they may seek affiliate designation from NAAB.

Near the end of REES, I found myself again spirited away to the now-familiar meeting room of KLE Tech’s architecture building to discuss accreditation options with Sharan Goudar and another colleague.

A text from Sharan encouraged me to finally craft this blog post, in fact. He responded to my recent blog Why India? Inspired by IUCEE and KLE Tech with a request for me to remember the architects:

Like Sharan, I, too, cherished the moments were shared in Hubli and I look forward to opportunities for more such moments, and a bit of hard (but fun and rewarding) research work, to boot!

My work with VIT Chennai and Dr. Nithya Venkatesan of the Internationalization Office may enable another trip to India, and I will make every effort to include a flight across to KLE Tech’s architecture department while I’m there.

These KLE architecture teachers are lovely, lovely people, and I look forward to getting to know them better and collaborating with them in both research and teaching.